Winner Hennephof by Site Practice

Last month we participated in a competition for affordable social housing for Talis in Nijmegen. The question was simple, but the answer quite hard: how can circular design be made possible for affordable housing?

The competition was won by Site Practice, who designed Hennephof, a wonderful design made of a wood and hempcrete structure. Our project FRAMED received an honorable mention, based on our critical position towards circular design, that we would love to share.

Circular design is still for the happy few, an architectural luxury and hard to achieve in the realm of afforable housing. Housing corporations have been put in the frontline of the transition towards a circular economy, but without any ammunition. Their financial capacity is continuously lowered and the legal demands in other sustainable ambitions - such as energy use - are raised at the same time.

Material analysis of material use by housing corporation Talis in Nijmegen.

If you look at the position of housing corporations in The Netherlands, they are a major player in the construction industry and this industry one of the main consumers of materials nation wide. Making a change in the use of materials for social housing does have a massive social impact.

Affordable housing does demand affordable materials and that does not match with the current demand for more sustainable building. Just as junk food is cheaper on the counter, but has massive hidden environmental costs, so does cheap building. The use of concrete as a structural base for projects already accounts for a huge amount of the material use and CO2 production of the construction industry.

Making a first transition to regenerative building materials is the first step in the material transition. Working with wooden structures already cuts out the first big chunk of the consumption. Finding circular alternatives for all those bits of the design that cant be replaced with regenerative alternatives is the second step.

Developing mutiple projects with the same reuseable, exchangeable building components creates a small scale, internal economy.

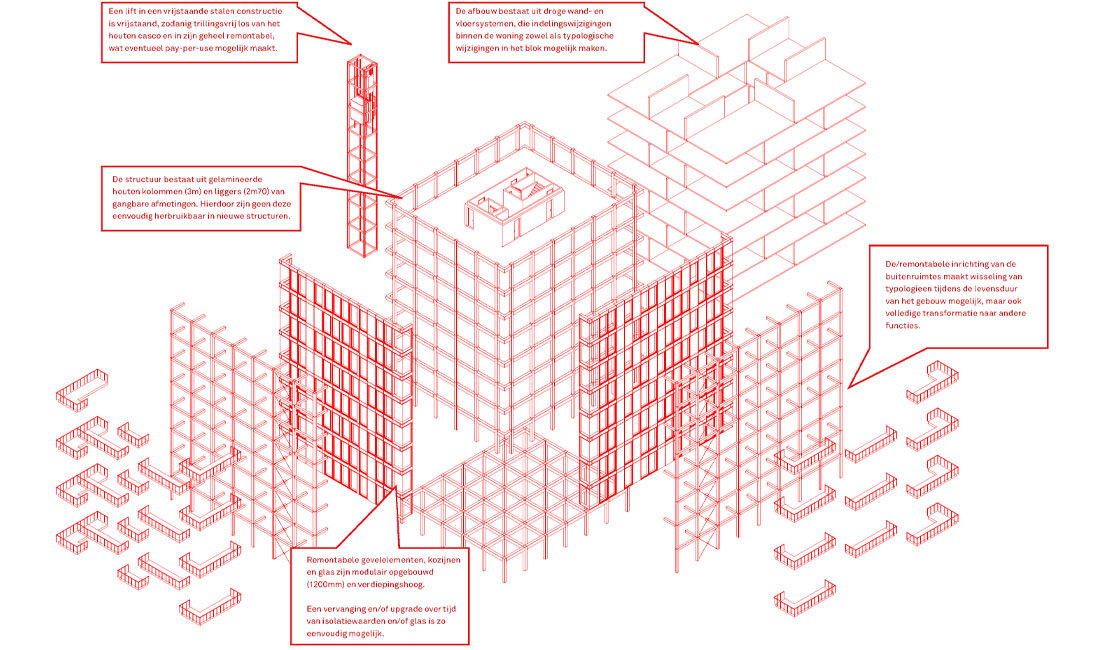

In the design, we have dived into alle the nitty gritty bits of the design, trying to find circular alternatives for all individual elements. In the selection we worked step by step.

Trying to find regenerative elements avoids thinking about reuseability at all, since these elements dont add to the depletion of materials period.

Secondly, trying to find reuseable alternatives for the left over elements fills in the last gaps. Making the main components of the buildingeasily exchangeable between projects, end-of-life elements of one project can be the ingredients for the new projects.

The demountability also comes with flexibility, that allows the corporations to change their buildings according to demographic and economical changes. This avoids building becoming obsolete due to non-technical reasons.

But these regenerative and circular materials come with a cost, that cant result in more expensive buildings. Or can it? Housing corporations do have a few tricks up their sleeve: they both have a long term commitment, a repeating initiative and an economy of scale. This combination makes it possible to make higher construction costs not translate directly into higher rents.

The long term commitment allows for a total cost of ownership approach, in which building costs and operating cost can be balanced. This way, choosing the right sustainable materials with higher initial costs, allow for lower overall costs. Using better materials makes for higher rest value at the end of their period of use, making them more susceptibale to reuse.

In the competition proposal, we calculated multiple alternatives for a view on building economies. By calculating even conservative rest values, positive financial results appeared, making it possible to transfer that result to more affordable rents.

Together with IGG Bouweconomie and Copper8, we developed circular financial models, in which the higher pre-investment into reusable building elements resulted with a higher return in its life span than a typical cradle-to-grave, linear approach. This ‘profit’ can be used to lower the actual rents in the building, creating a win-win of more sustainable, but also more affordable housing.

Because of the repeating initiative, exchange of materials between subsequent projects is possible, which makes it worth while developing details and materials that are easily demountable to reuseable. Elements from previous projects can be updated and developed into new elements for the next project.

The economy of scale makes it possible for housing corporations to create their own market. A threshold in the transition towards a circular economy is the base of trust needed in the transition. If you are not dependant on the external market to develop, but have enough projects to make an exchange of materials possible within the organisation itself, an economy with a closed wallet starts to appear.

But what if we combined forces with all housing corporations in the country, developing a small market of exchange between 300 housing dutch corporations? We can use our social real estate as material banks and create enough trust to make the transition towards a circular economy together.